Today’s almost random browsing brings about this series of connections, which links the capital of Venezuela to the highest ranking American killed in World War II, to fact that the act of making a mint julep with creme de menthe can be considered an abomination.

I had started out trying to figure out why Venezuela is named Venezuela. (This, in case you are wondering is primarily because I think “Caracas, Venezuela” might be the most fun place name of all to say.)

I had started out trying to figure out why Venezuela is named Venezuela. (This, in case you are wondering is primarily because I think “Caracas, Venezuela” might be the most fun place name of all to say.)

It turns out there is no definitive answer, but most people seem to agree that it’s some kind of language degradation based on Venice, and that the name can be traced back to Vespucci.

What I found out that is more important for this story, though, is that the proper full name of Venezuela is “República Bolivariana de Venezuela“, or “Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela” in English.

What I found out that is more important for this story, though, is that the proper full name of Venezuela is “República Bolivariana de Venezuela“, or “Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela” in English.

I’ve been slightly interested in the long form names of places and their related history ever since I found out (on a friend’s tour of Olvera Street) that the original full name of Los Angeles is “El Pueblo de Nuestra Señora la Reina de los Ángeles de la Porciuncula” or “The Town of Our Lady the Queen of the Angels of the ‘little portion'”. That makes for a much more intersting story than “it means City of the Angels”, I think.

Anyway, having found out about Venezuela’s full name, my interest in Bolívar was tweaked. I started by looking at the amazing list of places named after him (does anyone else have two countries named after them?)

Seeing this massive list, of course, triggered my interest in finding out more about Simón Bolívar. In general my education was pretty decent, and I have read widely enough that I can usually speak intelligently about most things at the cocktail party level, but I admit that all I really knew about Simón Bolívar was that he was a South American revolutionary of some kind. (Actually, sadly, in my mind he was also somehow linked to Simone de Beauvoir, who I do know a fair bit about. I suspect this is a little trick my mind played on me because of the sound of the names.)

Seeing this massive list, of course, triggered my interest in finding out more about Simón Bolívar. In general my education was pretty decent, and I have read widely enough that I can usually speak intelligently about most things at the cocktail party level, but I admit that all I really knew about Simón Bolívar was that he was a South American revolutionary of some kind. (Actually, sadly, in my mind he was also somehow linked to Simone de Beauvoir, who I do know a fair bit about. I suspect this is a little trick my mind played on me because of the sound of the names.)

So I read up on Simón Bolívar and found the history pretty interesting. I think I probably at least doubled my understanding of South American history in the 19th century in the process of searching and researching Bolívar. Oh, and speaking of full names, check this one out: Simón José Antonio de la Santísima Trinidad Bolívar y Ponte Palacios y Blanco. Damn, dude must have had two or three birth certificates.

In the course of doing this reading, however, things took a weird left turn when one of my searches turned up Simon Bolivar Buckner, or to be more specific Simon Bolivar Buckner, Sr.

In the course of doing this reading, however, things took a weird left turn when one of my searches turned up Simon Bolivar Buckner, or to be more specific Simon Bolivar Buckner, Sr.

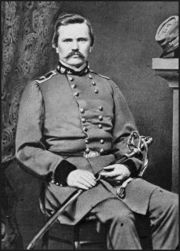

While it seems weird enough to find an upper class Southerner running around Kentucky named after a South American revolutionary and political leader, it gets a little weirder when you see that Buckner was involved in a lot of important history. A bit of research on him reveals that he was a general in the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War, the officer who yielded to Ulysses S. Grant‘s famous demand for “unconditional surrender” at the Battle of Fort Donelson in 1862. More than that, despite his name and his performance in the war, he afterwards became the governor of Kentucky, and even took a crack at the Vice Presidency. If you Google a bit you’ll also find he was a pretty inveterate racist as well. One thing I could not find was any commentary on why he had been named that way–surely somewhere the information is out there, but I was only doing cursory Google research.

I did find that Buckner had a son, who he creatively named Simon Bolivar Buckner, Jr.. Junior was also a military man, who rose to be a general in the American army in World War II.

He was a pretty successful career military man, who also spent some time as Commandant of Cadets at West Point (he was famously demanding of the students), and actually still has a couple of army bases named after him, including one in Okinawa.

He was also a famous racist, who opposed commanding black troops, and was not exactly circumspect in spreading his bigoted opinions around

“Buckner’s father, Confederate General Simon Bolivar Buckner, Sr., had surrendered to Brig. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant at Fort Donelson during the Civil War. Some have argued, perhaps wanting to prove that the apple does not fall far from the tree, that Buckner, Jr., was a racist and prejudiced against most minorities. Prior to his Pacific adventures, Buckner had commanded troops in Alaska and was derisive in his comments about African-American soldiers as well as native Alaskans.”

—Insight Column, WWII History Magazine, July 2005.. This is unforgivable, but perhaps understandable in the historical and geographic context.

On the plus side, he was a vigourous defender of the sanctity of the mint julep, on which more later.

It was in Okinawa where Buckner became the highest ranking American to have been killed during the Second World War. He was killed during the closing days of the Battle of Okinawa by ricocheting artillery fire.

It was in Okinawa where Buckner became the highest ranking American to have been killed during the Second World War. He was killed during the closing days of the Battle of Okinawa by ricocheting artillery fire.

He wasn’t the end of his line, though. A little Googling shows me that there is currently a Simon Bolivar Buckner IV (although he apparently goes by “Chip”). He’s an attorney in Missouri. From what I can tell looking around his web site, he’s much more the kind of guy I could get along with than his military ancestors were.

Chip has a page at his site about the Buckner family’s long relationship with the mint julep. Included there is his grandfather’s (that’s Junior, remember) julep recipe. You can click through for the recipe, but here’s a taste of the preface:

Chip has a page at his site about the Buckner family’s long relationship with the mint julep. Included there is his grandfather’s (that’s Junior, remember) julep recipe. You can click through for the recipe, but here’s a taste of the preface:

The preparation of the quintessence of gentlemanly beverages can be described only in like terms. A mint julep is not the product of a FORMULA. It is a CEREMONY and must be performed by a gentleman possessing a true sense of the artistic, a deep reverence for the ingredients and a proper appreciation of the occasion. It is a rite that must not be entrusted to a novice, a statistician, nor a Yankee. It is a heritage of the old South, an emblem of hospitality and a vehicle in which noble minds can travel together upon the flower-strewn paths of happy and congenial thought.

Of course I could enjoy that prose a lot more if I didn’t know that the “the flower-strewn paths of happy and congenial thought” were for white folks only…

Chip also note that he did once mess with the recipe, and was called out “slanderously” by his father

It was around the time that I was considering julep recipes that I realized what a weird chain I had been following. And so there you have it: Caracas to the independence of a huge chunk of South America, to the legend of Ulysses S. Grant, to death in Okinawa, to traditional juleps in Kansas City.

3 comments for “Hidden sequitors”