I just had a Thanksgiving conversation with my little

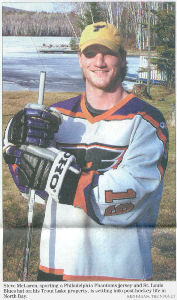

Normally I’m used to seeing my brother in papers in a little photo sting like this:

And that’s usually in some American paper. It’s been a long time since he was regularly in the hometown paper–probably since back in the day that he was the only local boy playing for our OHL team during the years they were champs.

Anyway, here’s what ran on the top of the paper:

I’ve scanned the article, which ran on the first page of the sport section. You can see the scans below, or just read the text, which follows:

Rolling with the punches

North Bay’s McLaren reflects on career as hockey enforcer

BY KEN PAGAN

The Nugget

When Steve McLaren was an up-and-comer with the North Bay Centennials, coach Bert Templeton helped instill the team-first, respect-the-game attitude McLaren carried through 11 seasons of pro hockey.

When Steve McLaren was an up-and-comer with the North Bay Centennials, coach Bert Templeton helped instill the team-first, respect-the-game attitude McLaren carried through 11 seasons of pro hockey.

Templeton, McLaren’s coach with the 1993-94 OHL champion Centennials, also told McLaren he’d have a shot at playing in the NHL some day.

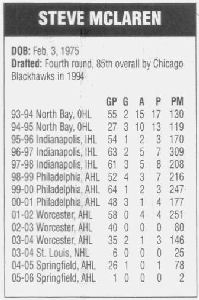

With Templeton serving as his agent, McLaren was drafted by the Chicago Blackhawks in the fourth round, 85th overall, in 1994.

Templeton’s influence remained as McLaren fought his way through the minor leagues — three seasons with the IHL’s Indianapolis Ice, three each with the AHL’s Philadelphia Phantoms and Worcester IceCats.

Finally, Dec. 13, 2003, McLaren was called up by the St. Louis Blues, who needed some protection for Doug Weight, Keith Tkachuk and Pavol Demitra with enforcer Reed Low injured.

The 28-year-old North Bay product made his NHI. debut Dec. 16 against the Columbus Blue Jackets, dropping the gloves on his second shift with Columbus tough guy Jody Shelley.

No sweat — McLaren had fought Shelley several times in the AHL.

But this was different.

After nine seasons earning a reputation as one of the top scrappers in the minors, McLaren finally got to spend five minutes in an NHL penalty box.

However, Templeton didn’t get to see it. The OHL coaching legend died 11 days earlier, Dec. 5, 2003.

“When I was with the Cents, Bert told me, ‘Stevie, if you can do one thing and be the best at it, you’ll make it to the NHL—you’re tough, keep at it,’” said McLaren, now a year out of pro hockey and back in North Bay.

“Bert was a guy who had respect. My first year with the Centennials. there were 14 rookies. He had our respect and everybody wanted to do what he said. That’s what made us the team we were.

“That’s what I took from him—everybody work for the same goal. When the coach has a plan, and everyone follows it, it’s going to work. Bert instilled the ‘we can DO this’ attitude in us.”

Before his official NHl call-up came, MCLaren had to endure an eight-hour bus ride from Norfolk. Va., to Wilkes-Barre, Penn., and he couldn’t sleep, thinking he might be getting the call. The next morning, Worcester IceCats coach Don Granato delivered the good news.

McLaren was off to The Show.

“I didn’t have anything — we were on the road with the AHL team, so I had a leather jacket, a golf shirt and a pair of slacks,” McLaren said. “Now I was in the NHL, so I had to go buy a new suit.”

A headline in The Hockey News highlighted the debut of ‘Stone Cold’ McLaren. Blues coach Joel Quenneville said McLaren was “wound tighter than a drum.”

* * *

It’s no secret what McLaren brought to a team — fists, fury, and willingness to stand up for teammates.

The six-foot, 225-pounder. who played all his minor hockey in North Bay and jumped to the OHL from the midget ‘AAA’ Trappers, made a name for himself throwing fists for the Centennials

When someone fought for Templeton, the coach played him—McLaren assumed a Centennials’ role held previously by Dennis Bonvie, Shawn Antoski and Mark Major, all of whom made the NHL.

Perhaps fighting for Templeton had something to do with longevity as a tough guy in the pro game — not many enforcers last 11 years.

“Bonvie’s one of the only guys still playing from when I started,” said McLaren. “Most of the guys I started with didn’t last longer than two or three years. And a lot more came and went.

“It’s good that I played that long as one of the top heavyweights, but it’s not so good I played that long as one of the top heavyweights and didn’t play in the NHL that much.

“I got there, but …

The enforcer’s role during McLaren’s day wasn’t easy. In the pre-lockout era, players like McLaren were an essential part of a team.

And they were expected to fight, with no days off. In 508 pro games, he scored 17 goals. 40 points and racked up 1,884 penalty minutes.

Including pre-season games during 11 NHL training camps, McLaren said he fought 250 times.

A tough way to make a living, perhaps, but he thrived in the role.

“You try not to think about it,” McLaren said of his approach. “A lot of guys have said they’d think about the tight the next day and wouldn’t sleep. Sometimes, you know you’re going to fight a guy a week ahead of time — it’s almost like boxing.

“I just tried not to think about it, and remind yourself that if you’re in a position when something bad happens, the linesmen jump in anyway. You can take that hit and break something, but if it’s bad, the linesmen will jump in — it’s not like a street fight where the guy is going to jump on you and try and kill you.

“And I always taught myself that, if it’s not going well, I’m strong enough to grab the guy to at least take him down.”

McLaren fought some of the toughest of his era, many on several occasions—Bonvie, Shelley, Aaron Downey. Every enforcer in the AHL had to get through him.

He even dropped the mitts on Eric Lindros when the Philadelphia Flyers franchise player coss-checked him in training camp.

(The toughest guy he faced? Hard to pick — they’re all tough, but he mentions Bonvie.)

Fighting is part of the game, and McLaren took pride in his role.

“I scored 17 goals, and I don’t even know how I scored them but I can tell you every punch and every fight,” he said. “In my case, and I think in a lot of cases, I could feel the team was behind me.

“A lot of times, after I’d fight, I’d come off and it would swing the tide of the game. The guys would say, ‘All right, Stevie just pumped that guy. Let’s go, boys!’ It would get the guys pumped and that’s the swing in the game right there.”

An enforcer doesn’t last 11 seasons with four NHL organizations by being dirty. McLaren took pride in being an honest, straight-up enforcer, and preferred doing his business with the same. He had no use for supposed enforcers who chose to pick their spots.

“There’s a lot of respect between tough guys and they all know, if they do something, they have to face the other tough guys,” he said.

“The problem is, the guys who aren’t tough guys who are running around and sticking people — the tough guy can’t go to him and do anything. If there was no instigator rule, and the team’s tough guy could take care of it, nobody would be getting a stick in the head.

“I think the tough guys take some of the chippiness out, because it settles things down. Everybody knows, ‘they have that guy and if we do something stupid, he’s coming.’”

* * *

Looking back, McLaren obviously wishes he would have got the NHL call earlier. But in many cases, for enforcers at least, the NHL call-up depends on the organization’s needs and being in the right place at the right time.

Looking back, McLaren obviously wishes he would have got the NHL call earlier. But in many cases, for enforcers at least, the NHL call-up depends on the organization’s needs and being in the right place at the right time.

In Chicago, the Blackhawks had Cam Russell, Bob Probert, and Jim Cumrnins. Philadelphia had Todd Fedoruk and Sandy McCarthy, as well as Bonvie, who was McLaren’s AHL teammate.

While with Philadelphia, McLaren recalls nearly being called up from the Phantoms, when Fedoruk was hurt.

Phantoms coach Bill Barber pushed for the call-up, as did Flyers assistant GM Paul Holmgren, but GM Rob Clarke didn’t approve, labeling McLaren their “slugger in the minors,” according to McLaren.

It wasn’t until McLaren realized the Flyers didn’t have a spot for him on the NHL team he decided to find a new organization.

Barber, a Hall of Famer from Callander, confirmed the theory.

“I pushed for it — I would have loved to have seen him up with the NHL team,” said Barber, now a Tampa Bay Lightning executive. “He deserved that chance just for what he brought to the AHL team. If it was up to me, he would have been up there.”

Barber coached McLaren for two seasons with the Phantoms, and was also instrumental in bringing McLaren into the Lightning organization with the AHL’s Springfield Falcons in 2004-05.

“Steve’s a good team man,” Barber said. “He always came in and played hard and it was never about playing for himself or his own situation. He was a quality guy you could count on game in and game out.

“He was a really good fighter. He fought all the heavyweights and always held his own against the top guys. I’m glad he got a taste of the NHL. He should be proud of his career.”

McLaren, who also credits former Trappers coaches Larry Keenan and Randy Sandvik for his development, lasted six games in the NHL, before suffering a concussion in a second fight with Shelley, Dec. 29, 2003.

Sticking around for more than just one NHL game was an important goal.

“The big thing was, I wanted to stay and play — I didn’t want to be that guy who only played one game and the team figured it was a mistake,” he said. “Had I not got hurt, I might have stayed the rest of the year.”

In fact, during the Christmas break, he said Mellanby approached him and asked of his salary.

“I told him what I was getting paid, but I was wondering, ‘why did he ask—did I forget to give the trainers a tip or something?’ But he said he went to the team and he, Doug Weight, Chris Pronger and Keith Tkachuk were going to pay my salary to keep me there if the team wanted to send me down.”

In the NHL, he fought five times — twice against Shelley and once each against Chicago’s Ryan Vandenbussche and Johnathan Aitken, and Colorado’s Peter Worrell.

“I’d ask Tkachuk before every game —‘Walt (Tkachuk’s nickname), is there anybody you want me to look after?’ And he’d tell me, but I already knew who it was and I knew I was fighting them anyway. That talk helped him, though.”

After the concussion, he never got another NHL shot.

McLaren returned to Worcester while recuperating and collecting his NHL salary for six weeks, before deciding to get back in the lineup — Worcester was facing three teams with tough heavyweights, and his teammates needed someone to fight.

The following year, the NHL was locked out.

McLaren played 26 games with Springfield, but came down with a case of mononucleosis, which drained him.

He was unable to train at full strength in the off-season prior to 2005-06, and Springfield coach Dirk Graham was reluctant to put him at risk until he was ready.

By that time, pro hockey had changed — more emphasis on speed, skill and special teams and less room for enforcers. With AHL rosters limited to four veterans with 260 games of experience, AHL teams were opting for up-and-coming enforcers, if any.

McLaren noticed the change in the game in his final few years.

“With teams now, it doesn’t seem there’s that support for the tough guy,” he said. “It’s not so much a team feeling, it’s more like players are being put together to form a team. You can’t do that. The guys have to play together for awhile to become a team.

“Now, they’re mixing players up so much, you’re not getting that team feeling. At least I didn’t feel it as much as when I started. I’m a big team guy.”

* * *

At 32, McLaren is starting a new chapter. He and his wife, Jennifer, were married in 1998 and have a home on Trout Lake. This past winter, he got the most out of his snowmobile and is now anticipating the spring melt so he can get the boat and dock in.

At 32, McLaren is starting a new chapter. He and his wife, Jennifer, were married in 1998 and have a home on Trout Lake. This past winter, he got the most out of his snowmobile and is now anticipating the spring melt so he can get the boat and dock in.

Last weekend marked a full year out of pro hockey, although he did dabble with friends in men’s league this season. (He’s got the hands back, too — a three-game goal-scoring streak in the Big Brothers tournament last weekend).

In his first year away, there was a tendency to miss the hockey lifestyle.

“I liked standing up for my buddies,” he said. “I’m that type of guy. And I miss having 30 buddies to go hang out with every morning for the rest of the day.”

In his next chapter, he hopes to go from fighting tough guys to fighting fires. Through the Professional Hockey Players’ Association’s career enhancement program, McLaren enrolled in an on-line firefighter’s course.

He’s just finishing up the theoretical studies, and is looking forward to hands-on training with members of the North Bay fire department.

“I would love to spend the rest of my life here,” he said. “I love the community and I love the area, and I have some history here. So, if it doesn’t work out with firefighting, I’ll be out putting some applications in somewhere.”

Through all the battles over 13 years, McLaren escaped relatively unscathed.

There were three documented concussions, a broken nose, a broken jaw, some separated shoulders, but he has a clean bill of health.

Aside from blood from the broken nose, he said he was never cut in any of the 250 fights. And most surprisingly, this hockey tough guy still has all his teeth.

“That’s the thing they say about hockey players — banged-up noses and no teeth,” he said. “I still have all my teeth, but I have the banged-up nose to go with them, though.”

15 comments for “Steve In The Hometown Paper”