I noticed a couple of interesting–at least to me–stories in the news recently about some really old books.

By far the more sensational story was the one about Codex Gigas, or Devil’s Bible, being put on display in Prague.

That fact that it’s on display is perhaps less interesting than the fact that it exists at all. There’s quite a legend around the book, which could be summarized like this:

According to legend the scribe was a monk who breached his monastic code and was sentenced to be walled up alive. In order to forbear this harsh penalty he promised to create in one single night a book to glorify the monastery forever, including all human knowledge. Near midnight he became sure that he could not complete this task alone, so he sold his soul to the devil for help. The devil completed the manuscript and the monk added the devil’s picture out of gratitude for his aid.

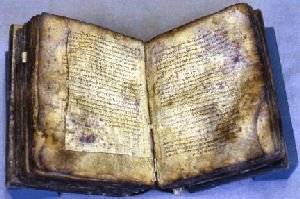

So, what kind of book could glorify a monastery forever? Well, it’s pretty much the biggest (as you might have guessed from the name) existing manuscript from medieval times. It’s 36.2″ tall, 19.7″ wide, and 8.6″ thick. It’s 320

You just know I’m going to find a way to mix this thing into my “Dogs and Sorcerers” story, right?

The other big “really old book” story recently was the one about the family in France who found the only existing copy of some of Archimedes‘ works sitting in their closet. Obviously that was a big pay day for them–they got $2,000,000 for it–but the real story here is that the text shows that Archimedes was on his way to inventing calculus about 2000 years before Newton and Leibniz managed it. In your face Isaac!

Of course, when I say “surviving copy” I actually mean something much more interesting than an old transcription:

Archimedes wrote his manuscript on a papyrus scroll 2,200 years ago. At an unknown later time, someone copied the text from papyrus to animal-skin parchment. Then, 700 years ago, a monk needed parchment for a new prayer book. He pulled the copy of Archimedes’ book off the shelf, cut the pages in half, rotated them 90 degrees, and scraped the surface to remove the ink, creating a palimpsest—fresh writing material made by clearing away older text. Then he wrote his prayers on the nearly-clean pages.

The article has some interesting details on the works, and on the kinds of document studies they had to do over the last nine years to recover the texts from the book.

First, intensive conservation and restoration stabilized the condition of the book itself. Then the researchers took digital pictures of it in different wavelengths of light, creating a multi-spectral image that could be manipulated to reveal the text by Archimedes. On four of the pages, forged paintings covered the entire text, so the researchers used x-ray fluorescence imaging to peek beneath the paintings and decipher the obscured text.

Check it out if you’re a Greek geek, a math geek, or a document studies geek.