I was recently in a discussion of books as art object. Usually when I’m in a conversation like that it’s about fine limited editions, but this time it was about books that are works of art in a more conventional sense.

I cited the Codex Seraphinianus, and the person I was talking to cited A Humument.

I admit I was pretty ignorant of the work, but I did recall seeing it mentioned recently at Eddie Campbell‘s blog. (Recall Campbell is oft mentioned here.)

Well, the conversation was enough to get me digging, and then Campbell started adding fuel to the fire…

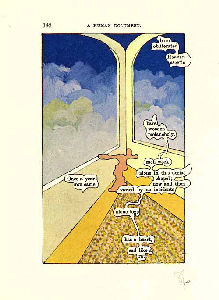

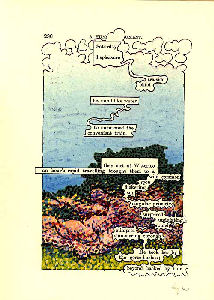

A Humument by Tom Phillips is a ‘treatment’ of a copy of the 1892 novel, A Human Document by one WH Mallock, presumably selected mostly for its anonymity. Phillips has taken each printed page of the original and converted it to his own purposes. The process begins with the selection of words and phrases from the text on the page to arrive at a new text. The resulting new text is by turns poetic:

‘the cakes and cream and- pleasures of life, and- butterflies-and her lips- her voice-and- words broken- And- my real- you’

and ribald:

‘The Princess with effusion held out a wrinkled- pologe- Grenville – scanned the sofa- to see- Miss Markham,- raising her- dress- half parted’

and later in his piece, this:

A Humument is usually described as an ‘artist’s book’, a medium which perhaps begins with Max Ernst’s collage novels. And within that medium the idea of altering earlier texts is not unique; there are some examples here (the ‘Altered Page’ exhibition) including somebody’s ‘treatment’ of the Yellow Pages. A Humument has its own particular relationship to narrative. To begin with, the characters of the original novel exist as marine life beneath the typographical surface, their movements occasionally catching the light by way of a name selected by Phillips for his new texts. But there is more than that. Phillips contrives to create an entirely new character whose existence is not even hinted in the original. This is Bill Toge (his surname formed from the four-letter sequence found only in ‘together’ and ‘altogether’), a casualty of love stumbling through the book.

‘The shyness of -toge- he looked- under – her dress- -anemones arrested- him— and a woman’s well poised eagerness”

and:

‘toge- accepted his -thrown value–and recognized yesterday- had to laugh’.

This, the underlying source text and a small assortment of visual cues, such as a window that Toge is usually sitting near to, even though there is no cartoonist’s continuity about what Toge is suppose to look like, just a few typographical rules that hold him ‘together’, bind the 366 pages of the ‘novel’ into a singular reading experience. By the end of it, Toge and his neuroses are real enough. (Phillips once said that when he arrives in a new town he tends to check the phone book in the vague expectation of finding a real Bill Toge.)

If that’s enough to get you fascinated as well, you can see the contents of the 1970 edition at Phillips’ web site, or even more obviously at his site Humument.com which, in addition to the gallery also contains a bunch of essays on the work and related topics.

Alternately, you could just order a copy of the book and check it out for yourself. Or if you really get into it, you can check out Phillips’ online gallery/store and maybe order a limited print of one of the pages…

Phillips has a bunch of other interesting projects, by the way. Check out 20 Sites n Years, which is a pretty cool project to photograph 20 sites annually over many years. (This one was pointed out by artist John Coulthart in his appreciation of Phillips–also where I found out that my music collection already includes art by Phillips. I think that means Phillips is no more than two degrees of separation away from every cool musician from the 70s.)

And it seems there are lots of other people doing the same kind of work now. An example.

At the end of the day, I’d rather own a copy of the Codex, but I surely did read through Phillips’ book online