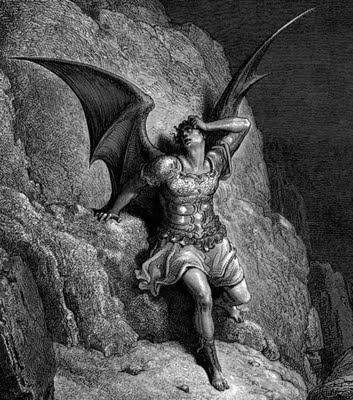

A couple of years back I ran through several variations on the Lucifer character / story that appeal to me. You may recall Part 1, Part 2, and Part 3.

In doing some reading last night in The Eldritch Dark‘s archive of Clark Ashton Smith‘s poety

The first is a sonnet, and as such is short enough that I can just throw the whole thing here:

A Vision of Lucifer

I saw a shape with human form and face,

If such should in apotheosis stand:

Deep in the shadows of a desolate land

His burning feet obtained colossal base,

And spheral on the lonely arc of space,

His head, a menace unto heavens unspanned,

Arose with towered eyes that might command

The sunless, blank horizon of that place.And straight I knew him for the mystic one

That is the brother, born of human dream,

Of man rebellious at an unknown rod;

The mind’s ideal, and the spirit’s sun;

A column of clear tame, in lands extreme,

Set opposite the darkness that is God.

Aside from the all the obvious work with light/dark and sun/darkness imagery, and the whole moral inversion thing, what fascinates me here is the casting of Lucifer as a kind of Romantic ideal–something embodying the dreams of humanity rebelling against the notion of some unknown rod, and using the mind’s ideal to bring light into the darkness. I can almost read that as Lucifer standing in as the symbol of a kind of Enlightenment urge to set aside the comfort of faith, and willingness to live with ignorance–in the dark–and instead rebel against that by taming the extreme lands and bringing light to the darkness. Not bad for a couple of lines.

The other view of Nick that Smith’s poetry brings us is slightly different, in the much longer Satan Unrepentant. This one’s too long to reproduce here in its entirety, but it’s not epic or anything–you can see it all at The Eldritch Dark.

In this case the view of Satan is closer perhaps to Brust’s–no different in kind to God, but just less powerful, and not willing to cede that this makes the kind of difference that should grant rulership and preeminence. And, of course, like the other interesting cases, Smith’s Satan is unrepentant, and unbowed. “I still endure, / Abased, majestic, fallen, beautiful, / And unregretful in the doubted dark”. Yes, that’s how it should be, isn’t it?

Smith works the light/dark thing again here, and the repeating sun/flame imagery, although this time letting God have the rhythmic, perfect music of the suns, and giving Satan the “discords of the dark”. Don’t think that God’s the good guy in this case, though–we’re hearing Satan’s side of the story, of course, but the picture he paints of a tyrant, ravenous and insatiable for control, who built his throne on injustice, and rules whimsically by main force isn’t exactly a glorious one.

Satan claims to be equally strong-willed (if less powerful) and of the same essential nature as God, and since he has an “unsubmissive brow and lifted mind” the tyrant God keeps him trapped in darkness as a dreadful secret, because “All tyrants fear whom they may not destroy”. Apparently what Satan thinks God fears is just his rebellion: “strong in tyranny, / The despot trembles that I stand opposed!”

And so, he waits… bloodied, but unbowed, as ’twere, for something to bring God down “Whether through His mischance or mine own deed, / Or rise of other and extremer Strength”. Apparently the eventual, and Satan thinks inevitable, ending of God will justify the rebellion. Certainly were it to come about because of some other stronger power arising, that would justify a rebellion against one who holds power by main strength, but claims the strength provides legitimacy as Supreme–someone stronger coming along would rupture that claim, and with irony. As, of course, would being brought down by some lesser power, really.

There are lots of fascinating readings of this. You could take Satan at his word and read the poem as a statement of enduring principle from an unjustly exiled rebel. You could assume that the facts are more-or-less as presented, but with Satan playing the role of your stereotypical unreliable narrator–and who better for that role? Maybe he isn’t quite so unjustly exiled? He’s certainly arrogant and proud in his self-description. Maybe he’s wrong (either knowingly or unknowingly) in his claim to be of the same stuff as God–if that were a prideful mistake then lots of things would take a very different colour. God’s injust tyranny, for example, might be the kind of jailhouse complaint about righteous authority one always hears from criminals.

And then there’s the ways you can read that last section about the waiting–is he waiting patiently for freedom, or for his turn to rule? And if he is the unreliable narrator, and God’s not the tyrant, but the righteous jailer, then what does it mean that Satan waits so patiently?

I suppose I could argue that this is a horror piece, with the horror coming with the notion that Satan may be right that God’s number will one day be up, and the looming worry about what that might mean–especially if Satan’s turn comes next, and he’s not the hero of the piece that he paints himself.

I could equally argue that it’s an examination of Satan’s folly–that his inability to see the difference in kind between himself and the creator deludes him into thinking that his day will come, when it never actually will. And that this willful pride and self-delusion traps him in the darkness more than any tyrants actions.

And, of course, those are just the readings where we can’t depend on the narrator. There’s also the surface reading of the proud and unrepentant rebel cast out by a fearful tyrant who can’t stand the notion of rebellion at all.

Smith is neither Santayana nor Milton, but he does manage a few impressive lines, and he leaves enough room for some interesting interpretations of what his Satan is all about.

3 comments for “Proud and Unrepentant: Part 4”